Lamer said closer analysis can find that FEMA’s approximated maps can overestimate flood risks — something clients are usually hoping for.

“I’ve had lenders say, ‘Prove to me we’re out of the floodplain’ and we do the work and you’re 30 feet above the river,” Lamer said of FEMA’s original mapping. “That’s how inaccurate these maps are.”

Across the nation, appeals to adjust FEMA maps are common before and after FEMA’s maps are finalized.

Pralle, the Syracuse professor who has studied flood policy, and Devin Lea, another academic, reviewed five years of data on how FEMA maps are revised. They found that over 20,000 buildings in 255 counties across the U.S. were re-mapped outside of special flood hazard zones from 2013-2017 through several appeals processes. More than 700,000 buildings remained in special hazard flood areas in those counties.

The agency approves the vast majority of map amendments, Pralle said, and Lamer, who has worked on hundreds of map amendment applications, said he’s only had one rejection. In that sense, Camp Mystic’s 92% success rate with exemptions is not an anomaly, but the norm.

“You don’t submit it if it’s not going to get approved,” Lamer explained, because there is no financial incentive for clients to continue with the process unless the data shows their flood exposure is less than what FEMA has determined.

While FEMA’s high-risk flood zones often grow after the agency finalizes new maps, property owners and communities can push to shrink those zones later.

Changes to special flood hazard zones are more common “where median home values are higher, buildings are newer, and percentage of white populations are higher,” according to a study published in Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy by Pralle and Lea.

The pair’s research suggests the appeals system’s incentives align to shrink federal flood maps.

“FEMA does not have the resources to go out and double-check” in the field, Pralle said.

A FEMA spokesperson said the agency reviewed Camp Mystic’s cases and the elevation data submitted, in accordance with its policies. The agency noted that the amendment approvals “do not materially change the reality of the risk and dangers of flooding.”

Storms like those that devastated Camp Mystic are expected to happen more often in a warming world. To shore up existing blind spots, independent organizations are building data-rich tools to better predict the growing risk of intense rainfall.

For example, First Street incorporates global climate models to forecast weather extremes and incorporate those into its risk maps. The firm provides data and analytics to individuals, banks, investors and governments, among others, for a fee.

Nationally, its analysis found more than twice as many buildings fell within 100-year floodplains compared to FEMA maps. The discrepancy was overwhelmingly due to heavy precipitation risk that FEMA maps didn’t capture, Porter said.

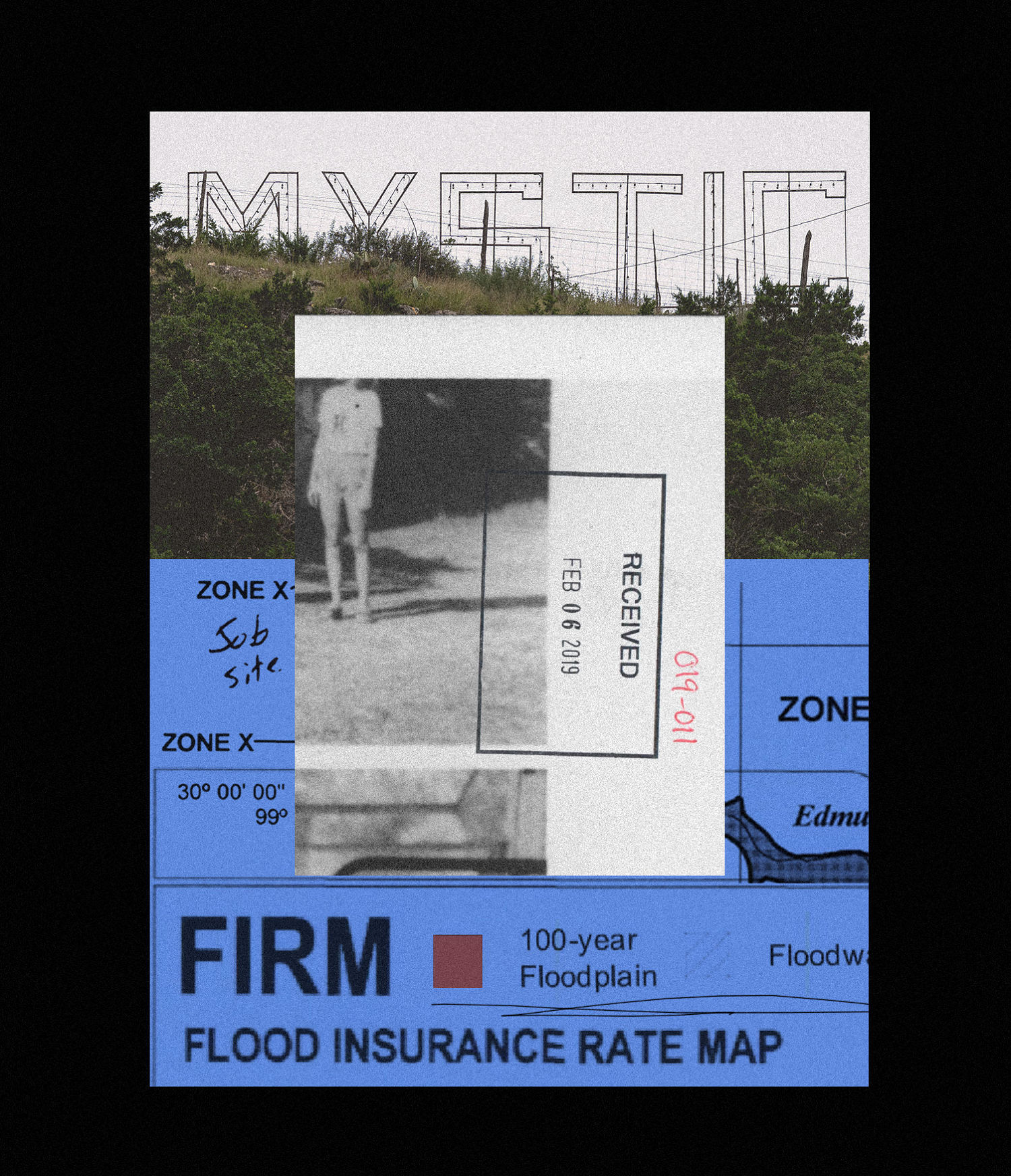

The firm’s mapping of Camp Mystic’s 100-year flood zone shows that portions of both the older and new camp sites would be flooded in such an event. In some areas, the flood zone is outside of both Hewitt’s and FEMA’s unstudied 100-year floodplain; in other areas, it’s much narrower and hews closer to the work of Hewitt Engineering.

Steubing, of the floodplain association, said early indications suggested that the flooding that occurred on July 4 was an event that could be expected once in 800 years, but more work is needed and several engineering firms continue to evaluate the flood’s extent. It’s not yet clear how precisely the extent of flooding corresponded to the various risk maps.

Although First Street’s mapping better incorporates climate risk, it has limitations of its own — namely, that it lacks the kind of detailed survey and streamflow analysis work apparently completed by Hewitt.

“We don’t have feet on the ground,” Porter said.

In an ideal system, flood mapping would combine detailed on-the-ground engineering, modern rainfall and streamflow data and predictions about future climate risk. Steubing said floodplain managers need more dynamic tools that depict different flooding scenarios — like fast-falling deluges that blanket small areas, and less rapid but persistent storms that last days. That would help determine risk much more precisely for individual communities.

Texas is trying to address a slew of historic data gaps to move in that direction, Steubing said.

But much of the state, like portions of the landscape near Camp Mystic, has never been studied in detail or hasn’t been mapped at all.

To address those gaps, the state has helped fund a new program with FEMA, called Base Level Engineering. The effort focuses on using high-resolution LiDAR data and modern modeling to estimate base flood levels in places that haven’t been studied closely. The maps are meant to complement, not replace FEMA’s FIRM maps. The new mapping, which is now available statewide and covers the area near Camp Mystic, was released about six months ago, Steubing said, and represents the kind of next-level model that could help prevent the next disaster.