In the heady last years of the 20th century, when inflation was low, interest rates were modest and employment levels high, the term “new economy” took on a whole new meaning.

It was coined in the 1980s to describe the transition from a manufacturing industry to a new, technology- and service-based economy. Today, we might call it the “third Industrial Revolution”, the “Digital Revolution” or the “Information Age”.

The “end of history”, as Francis Fukuyama called the victory of liberal democracy over totalitarian communism in the Cold War, cast a rosy light. Optimism and idealism pervaded the world as the internet – a true democratisation of information and communication – spread like wildfire.

Read: The train that never came – how maglev technology was derailed

As the tech-heavy Nasdaq began to offer online trading, “new economy” became a byword for confidently hyperbolic projections, blow-out stock offerings and eye-watering price-earnings ratios. The technology industry valued growing reach (“eyeballs”, in the cant of the day) over old-fashioned concerns such as revenue and profitability.

“Build it, and they will come,” a misquote appropriated from a 1989 Hollywood blockbuster, Field of Dreams, passed for business wisdom in the dot-com era.

Silicon Valley’s tech moguls had crafted a utopian vision of a future with smart homes, walkable cities, online communities, informal offices, green energy, high-speed mass transit, peer-to-peer file sharing and just-in-time supply chains.

Bubbles burst

The bubble burst, as bubbles must, in March 2000. Stock markets crashed. An avalanche of companies built on little but thrilling ideas and youthful energy went bankrupt.

The economy went into recession. Silicon Valley went into depression. The crash was epic. But the vision of a technology-fuelled remade world remained, and the industry was eager for something new. It needed new heroes and fresh ideas.

It was in this post-crash funk, in January 2001, that rumours of a new product, code-named “Ginger”, began to do the rounds.

Nobody had seen it. Nobody knew what it was, but it was created by an award-winning inventor/impresario who had attained considerable fame in medical devices and amateur robotics and was well-known for promoting science, technology, engineering and mathematics education to students.

His name was Dean Kamen.

He pioneered the intravenous drug infusion pump that is now standard equipment beside every hospital bed. He invented a wearable insulin pump known as the AutoSyringe, and the HomeChoice portable dialysis machine.

He also had a wild image. Born in 1951, he was already earning US$60 000 for his engineering ideas by the time he finished high school. He went to college, but spent most of his time researching the AutoSyringe instead and never graduated.

His house in New Hampshire was peak eccentric inventor weirdness: a four-storey hexagonal structure complete with a full-size steam engine, once owned by Henry Ford, in the atrium.

He owned (and still owns) a private island called North Dumpling, in the Long Island Sound, a mile off the coast of Connecticut. It has a dinkum lighthouse on it, and Kamen would joke about founding his own country.

Though he thought it wasteful that an 1 800kg vehicle should be necessary to transport a 70kg human being around, he was an accomplished pilot who owned a business jet and routinely travelled around in one of his three personal helicopters.

Party trick

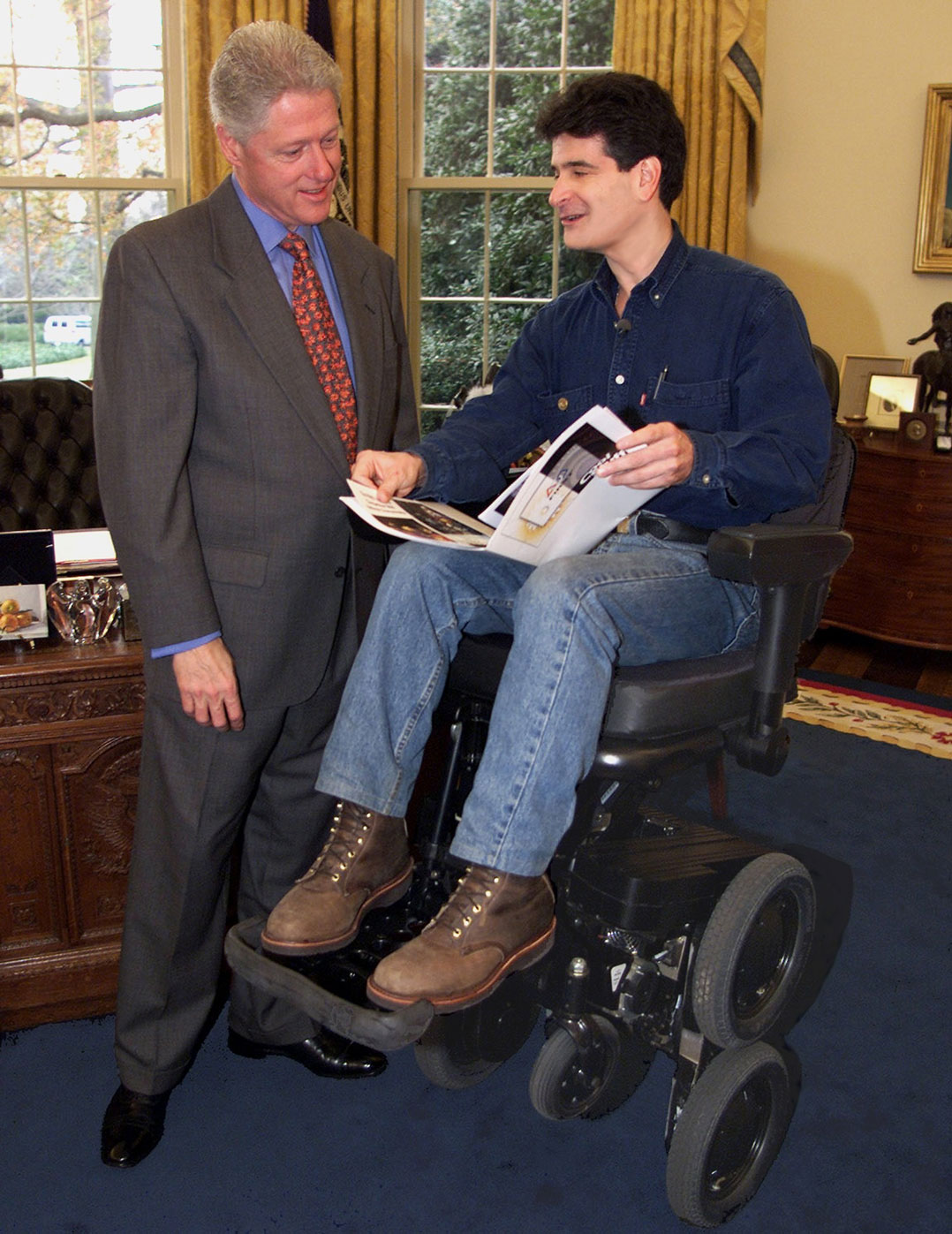

Most importantly, he had designed and built an all-terrain electric wheelchair, called the iBOT. Its party trick was the ability to lift itself up and balance on two wheels, to raise the occupant to eye-level with others.

Ginger, said Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, an early investor in the secret project, “is a product so revolutionary, you’ll have no problem selling it”.

“If enough people see the machine, you won’t have to convince them to architect cities around it. It’ll just happen,” gushed Apple talisman Steve Jobs, adding that it was as big a deal as the PC.

John Doerr, venture capitalist with Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, the famous firm behind Compaq, Netscape, America Online and Amazon.com, which also backed Ginger, said it might be bigger than the internet.

“[It will] sweep over the world and change lives, cities and ways of thinking,” promised Steve Kemper, the only journalist to have seen “it” prior to its release. He was writing a book about it, for which he received a honking $250 000 advance from Harvard Business School Press, without either the book’s editor or its publisher knowing what “it” was.

“Touted as bigger than the internet or PC,” wrote tech journalist PJ Mark, who broke the news when details of the book deal leaked.

‘Ginger’

Kamen’s new invention built on his experience with the gyroscopic stabiliser that was central to the iBOT wheelchair, which he had launched in 1999.

With more than $100-million in backing from medical products company Johnson & Johnson, according to reports at the time, the iBOT, besides rising to balance on two wheels, could also tackle rough terrain and even – if the occupant was specially trained – climb stairs.

His codename for the iBOT had been “Fred”, suggesting the effortless mobility of famed 1930s dancer Fred Astaire. “Ginger”, his new invention, took its name from Astaire’s frequent dance partner, Ginger Rodgers.

Read: The colossal carbon capture con

What Kamen eventually unveiled was, immediately, underwhelming.

The Segway Personal Transporter (PT) was a self-stabilising platform with handlebars, with large wheels side-by-side. The stabilising computer controlled the device’s movement: lean forward, and the machine rolls forwards. Lean back, and the machine slows down and stops.

The editor-in-chief of ExtremeTech magazine, the late Bill Machrone, took a sceptical, almost cynical view. Under the headline, “Ginger Unveiled – It’s a Scooter!”, he asked: “Cool technology, but will it change anything?”

“An electric scooter is a bit of a disappointment to those who were hoping for a Back to the Future hoverboard or a Stirling engine-powered device that would vastly reduce gasoline consumption,” he wrote.

To be fair to Kamen, he added: “Kamen himself has tried to minimise anticipation. A statement on his company’s website claimed that the rumours and speculation had far exceeded the device itself.”

Machrone’s “meh” response was influential. He was famous as a former PC Magazine editor who pioneered the laboratory-style comparison style of product reviews, started PC Labs, and went on to found ZDNet and ZD Labs, for the same publishing company, Ziff-Davis.

Less technical media were more optimistic. Time magazine called it “reinventing the wheel”, and quoted Kamen saying it “will be to the car what the car was to the horse and buggy”.

Time wrote: “In the future he envisions, cars will be banished from urban centres to make room for millions of ‘empowered pedestrians’ – empowered, naturally, by Kamen’s brainchild.”

They weren’t.

A president falls

When it hit the market, the standard model Segway Personal Transporter cost $3 000. An industrial-strength model targeted at businesses like the US Postal Service, the National Parks Service and Amazon.com cost $8 000.

The original model had a steering control on the handlebars. It had three speed settings, between about 9km/h and 16km/h. The battery had a range of between 9km and 16km (coincidentally the inverse of its speed), and needed four to six hours to charge. If low battery warning was ignored, it would suddenly stop, flinging the hapless rider forwards.

US President George W Bush made headlines when he fell off a Segway at his family compound in New England in 2003. The company soon recommended safety gear, including helmets, be worn.

At the price, the Segway wasn’t for the everyman pedestrian. A Segway might be a cool toy for rich poseurs, but few people could splurge that kind of money on a bulky gadget that perhaps made cruising the promenade more efficient, but also need to be stored, charged, cleaned and serviced.

The machine never won over the average pedestrian.

Barely surviving

Despite a 2006 update that introduced a tilting control stick to make steering more natural, new features like regenerative braking, improved batteries, a security mode to discourage theft, and off-road models, it was struggling to make ends meet.

Kamen sold the Segway company in 2009 to British businessman Jimi Heselden. A year later, Heselden died when he (likely accidentally) rode his off-road Segway over a cliff.

Robert Brown bought the company out of Heselden’s estate in early 2013 for a meagre $9-million. The original backers had long since moved on.

By tightening supply chain contracts and focusing on markets like the National Parks Service, Amazon warehouses, police departments and shopping mall security outfits, he managed to keep the company afloat, and was delighted to offload it to Chinese manufacturer Ninebot in April 2015 for $75-million.

In August of that same year, a Segway would again hit the headlines when a cameraman riding one knocked over sprinter Usain Bolt at the IAAF World Championships in Beijing.

In 2020, Segway announced that it would end production of the Segway Personal Transporter.

Not that Ninebot wasn’t doing very well. The Segway PT made up only 1.5% of its revenues, but it had translated the Segway brand into great success with two-wheeled kick scooters, Vespa-style electric scooters, four-wheeled electric all-terrain vehicles and delivery robots.

Three alternatives

The idea of convenient, human-sized electric transport wasn’t wrong, but it never needed complicated and expensive gyroscopic balancing tricks.

Three alternatives met with all the success that the Segway never achieved, because they simplified the product and didn’t try to be all things to all people.

In 2018 alone, Ninebot sold 10 times as many electric kick-scooters as the 100 000 units Segway sold in 17 years.

Brown would later say that if he had anticipated the kick-scooter revolution, Segway would have been worth $10-billion. That estimate is on the mark: the global electric kick-scooter market was worth a staggering $6-billion in 2024, and is growing at 12%/year.

What’s more, riding a kick-scooter actually looks cool.

Even more cool is to use the Segway’s gyroscopic technology, but ditch the clumsy handlebars. The “hoverboard”, as it was (contentiously) called, is also worth over a billion dollars.

And for the rest of the market – the old, the heavy, and the infirm, who aren’t up to high-speed athletic sidewalk racing – there are four-wheeled electric mobility scooters. Valued at $3-billion in 2023, the global market will likely double in the next 10 years, fuelled by the US, where half of the world’s mobility scooters are sold.

Foreseeable

The failure of the Segway to change the world, and to spark the redesign of entire cities, should have been entirely foreseeable.

Kamen’s iBOT wheelchair sold a total of 500 units, for a per-unit R&D cost of $200 000.

Meanwhile, rival mobility companies sold tens of thousands of electric wheelchairs. Some had rough-road capabilities, like the iBOT. Some had stair-climbing capabilities like the iBOT, but using a track system. Many could raise occupants to eye-level, like the iBOT, but they did so simply by raising the seat on a scissor-lift mechanism instead of making the whole contraption balance on two computer-controlled wheels.

The Segway has often been described as “ahead of its time”. It wasn’t. It was unnecessarily complex. It was too clever by half, as the expression goes.

Yank out half the clever electronics, and return the wheels to their original gyroscopic function to keep a rider upright, and you have a far less expensive, more convenient and frankly, less nerdy-looking means of personal transport.

Give it four wheels and a seat, and you’re catering to the rest of the market, which just wants a comfortable way to get around.

A lot of products born of idealism and over-investment have failed spectacularly, but none has been as breathlessly awaited only to bitterly disappoint as the Segway Personal Transporter.

Get breaking news from TechCentral on WhatsApp. Sign up here.

- The author, Ivo Vegter, is a columnist for The Daily Friend and former technology journalist

- This article is part of a series about amazing technologies that promised to change the world, but did no such thing