Orla GuerinSenior International Correspondent in Gaziantep, Turkey

BBC

BBCThe pull of home can be strong – even when it is a place you can’t remember.

That is how it is for Ahmed, 18. He emerges from a mosque in the heart of Gaziantep in south-east Turkey – not far from the Syrian border – wearing a black T-shirt with “Syria” written on the front.

His family fled his homeland when he was five years old, but he is planning to go back in a year or two at most.

“I am impatient to get there,” he tells me. “I am trying to save money first, because wages in Syria are low.” Still, he insists the future will be better there.

“Syria will be rebuilt and it will be like gold,” he says.

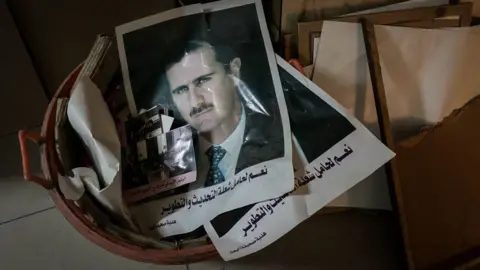

If he goes back, he will be following in the footsteps of more than half a million Syrians who have left Turkey since the ousting of Syria’s long-time dictator, Bashar al-Assad, in December 2024.

Many had been here since 2011, when civil war began devouring their country.

In the years that followed, Turkey became a safe haven, taking in more Syrians than any other country. The number reached 3.5 million at its peak, causing political tension and – on occasion – xenophobic attacks.

Officially, no Syrian will be forced to go, but some feel they are being pushed – by bureaucratic changes, and by a waning welcome.

Civil society organisations “are getting the message from the authorities that it’s time to go”, says a Syrian woman who did not want to be named.

“I have a lot of good Turkish friends. Even they and my neighbours have asked why I am still here. Of course we will go back, but in an organised way. If we all go back together, it will be chaos.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAya Mustafa, 32, is eager to leave – but not yet. We meet under a winter sun by the stone walls of a castle, which has towered over Gaziantep since the Byzantine era. Her hometown, Aleppo, is less than two hours’ drive away.

She says going back is a constant topic of conversation in the Syrian community.

“Every day, every hour, we speak about this point,” says Aya, whose family were lawyers and teachers back home, but had to start again in Turkey, baking and hairdressing to earn a living.

“We are talking about how we can return, and when, and what we can do. But there are many challenges, to be honest. Many families have children who were born here and can’t even speak Arabic.”

Then there is the level of destruction in new Syria – where war has done its worst – and where the interim president, Ahmed Al Sharaa, is a former senior leader of Al Qaeda who has worked to reinvent his image.

Aya saw the ruins of Aleppo for herself when she went back to visit. Her family home is still standing but now occupied by someone else.

“It’s a big decision to go back to Syria,” she says, “especially for people with elderly relatives. I have my grandmother and my disabled sister. We need the basics like electricity and water and jobs to survive there.”

For now, she says, her family can’t survive in Syria, but they will return in time.

“We believe that day will come,” she says, with a broad smile. “It will take some years [to rebuild]. But in the end, we will see everyone in Syria.”

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesA short drive away, we get a very different view from a Syrian family of four – father, mother and two teenage sons. The father – who does not want to be named – runs an aid organisation helping his fellow countrymen. Over glasses of tea and helpings of baklava, I ask if he and his family would move back. His response is swift and adamant.

“No, not for me and for my family,” he says. “And the same goes for my organisation. We have projects inside Syria, and we hope to extend that activity. But my family and my organisation will stay here in Turkey.”

Asked why, he lists problems with the economy, security, education and the health system. Syria’s interim government “hasn’t any experience to deal with the situation”, he tells me. “Some ask us to give them a chance, but one year has passed and the indications are not good.”

He too has visited the new Syria, and, like Aya, was not reassured. “The security situation is very bad,” he says. “Every day there are killings. Regardless of who the victims are, they have souls.”

His voice softens when he speaks of his 80-year-old father in Damascus, who hasn’t seen his grandsons for 12 years, and may never see them again.

For now, he and his family can remain in Turkey, but he’s already making contingency plans in case government policy changes.

“Plan A is that we will stay here in Turkey,” he says. “If we cannot, I’m thinking about plan B, C and even D. I am an engineer, always planning.”

None of those plans involve a return to Syria.

If going home is hard, staying in Turkey isn’t easy either. Syrians have “temporary protection” that comes with restrictions. They are not supposed to leave the cities where they are first registered. Work permits are hard to get, and many are in low paid jobs, living on the margins.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan – who backed the uprising against Assad – has insisted that no Syrian will be driven out, but refugee advocates say there are growing pressures beneath the surface.

They point to the ending of free medical care for Syrians from January, and new government regulations which make it more expensive to hire them.

“These new elements cast a shadow over how voluntary returns are,” says Metin Corabatir, who heads an independent Turkish research centre on asylum and migration, IGAM.

And he says presidential and parliamentary elections – due by 2028 – may be another threat for Syrians here.

“Normally President Erdogan is their main protector,” Mr Corabatir tells me. “He says they can stay as long as they want. And he repeated this after the regime changed. But if there is an election, and a political gain for the AKP [ruling party] to make, there might be some policy changes.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFresh elections could revive the xenophobic rhetoric that featured in the last polls, he warns. “Those feelings went to sleep,” he says, “but I am quite sure the infrastructure of this xenophobic attitude is still alive.”

On a cold grey morning at a border crossing an hour’s drive from Gaziantep the hills of Syria are visible, a short distance away.

Mahmud Sattouf and his wife Suad Helal are heading to their homeland – this time just for a visit. They have Turkish citizenship, so they will be able to return. For other Syrians, the journey is now one-way.

Mahmud, a teacher, is beaming with excitement.

“We are returning because we love our country,” he says. “It’s a great joy. I can’t describe it in words. As we say in English: ‘East, west, home is best’.”

He and Suad will move home in about a year, he tells us, when Syria is more settled, along with their four sons, and their families.

“I am 63,” he says, “but I don’t feel like I am an old man. I feel young. We are ready to rebuild our country.”

How will it feel to be back for good? I ask.

“I will be the most happy man in the world,” he says, and laughs.