Screen siren Brigitte Bardot, whose portrayals of free-spirited ingenues made her an international sex symbol and the pride of France, and who turned her back on movie stardom in 1973 to become an animal rights activist, has died, according to French media and Associated Press.

She was 91.

Bruno Jacquelin, of the Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the protection of animals, told The Associated Press that she died at her home in southern France. He did not provide a cause of death, and said no arrangements have yet been made for funeral or memorial services. She had been hospitalized last month after a period of ill health.

Leading tributes, French President Emmanuel Macron said Bardot “embodied a life of freedom” and lived a “French existence.” Jordan Bardella of the far-right National Rally party, which Bardot publicly supported in her later years, referred to her as a “passionate patriot” who represented “an entire era of French history.”

Bardot’s foundation paid tribute to her legacy on animal rights, from travelling to the Arctic ice floes to help baby seals, to lobbying for animal welfare legislation and securing convictions for perpetrators of animal abuse.

Her death comes two months after she underwent what her staff, in a statement to AFP, described as “minor surgery” for an unspecified ailment in October 2025.

At the time, Bardot quickly swatted away false online reports that she had died.

“I don’t know which imbecile launched this fake news regarding my disappearance, but know that I’m fine and have no intention of bowing out,” she had posted on X.

But a month later, in November 2025, Bardot was hospitalized again for what French news outlets described a “serious” health issue.

Born a brunette on Sept. 28, 1934, in Paris, Bardot became world famous after she dyed her hair blonde and starred in the 1956 movie “And God Created Woman,” which was directed by her first husband, Roger Vadim.

The provocative French melodrama about a voluptuous teenager who scandalizes Saint-Tropez was a box office smash both abroad and in the United States, despite mixed critical reviews and condemnation by watchdog groups like The National Legion of Decency.

Dubbed a “sex kitten” by British film producer Tony Tenser, Bardot broke through as the so-called sexual revolution was underway, women were embracing birth control, and many moviegoers were searching for racier fare.

French feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir called her a “locomotive of women’s history” and “the most liberated woman in post-war France” in a 1959 essay titled “Brigitte Bardot and the Lolita Syndrome.”

French President Charles de Gaulle declared that Bardot was a “French export as important as Renault cars.”

Meanwhile, BB, as the French affectionately called her, went on to appear in more than 40 movies, including a handful of Hollywood productions, before retiring from acting at age 39.

But before she retreated to her estate on the French Riviera to lead a far more reclusive life, Bardot bared it all in the pages of Playboy to mark her 40th birthday.

And soon she was championing a new cause.

“I gave my youth and my beauty to men,” Bardot later said, “but I give my wisdom and experience to animals.”

Bardot appealed to the Danish queen to halt the mass killings of dolphins in the Faroe Islands.

Bardot became a hero to animal rights activists. And in 1985, when France awarded her the Legion of Honor medal, Bardot insisted it was for her work to save animals — not for her movies.

“I take this Legion of Honor for my fight in favor of animals,” Bardot declared.

In 1986, the former actor founded the Brigitte Bardot Foundation and harnessed her fame to lead campaigns against, among other things, the eating of horse meat and the hunting of turtle doves in France.

In her later years, Bardot gravitated to far-right politics and was fined repeatedly for inciting racial hatred against Muslim immigrants to France, according to news reports.

In her 1996 memoir, Bardot outraged many fans by declaring her support for far-right National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen. Her fourth husband, businessman Bernard d’Ormale, had been an adviser to Le Pen.

The Nazis were occupying Paris when Bardot was growing up in a luxurious seven-bedroom apartment and dreaming of becoming a ballerina.

Raised by conservative Catholic parents, Bardot chafed against her upbringing. But she was allowed to take dance classes. And in 1950 she landed, at age 15, on the cover of Elle magazine after the editor spotted her at a train station.

That led to a movie audition the next year, where Bardot met Vadim, who was 24 at the time.

Despite the age difference, they fell in love. And over her parents’ objections, Bardot and Vadim married on Dec. 21, 1952, three months after her 18th birthday.

Bardot embarked on a movie career that, early on, included a small part in the 1953 Hollywood production “Act of Love,” starring Kirk Douglas.

Three years later, while shooting an Italian movie called “Mio figlio Nerone,” Bardot at the urging of the director dyed her hair blonde and turbocharged her career.

Bardot was box office gold and even won critical acclaim for her turns in internationally-produced movies like “The Truth” (1960) and “Viva Maria!” (1965). But she mostly steered clear of Hollywood, although she did play herself in the 1965 comedy “Dear Brigitte.”

Bardot did not think much of her own acting.

“I started out as a lousy actress and have remained one,” she reportedly said, according to The Guardian.

Bardot also recorded some 60 pop songs in the 1960s and 1970s, many of them in collaboration with French singer Serge Gainsbourg, with whom she had an affair while married to her third husband, German millionaire Gunter Sachs.

One of Bardot’s best-known musical forays was a cover of Stevie Wonder’s “You Are The Sunshine of My Life” with French singer Sacha Distel.

By her own admission, Bardot’s personal life was tempestuous.

Her marriage to Vadim began falling apart on the set of “And God Created Woman” when she embarked on an affair with her co-star Jean-Louis Trintignant.

It was one of many infidelities that Bardot has admitted to over the years.

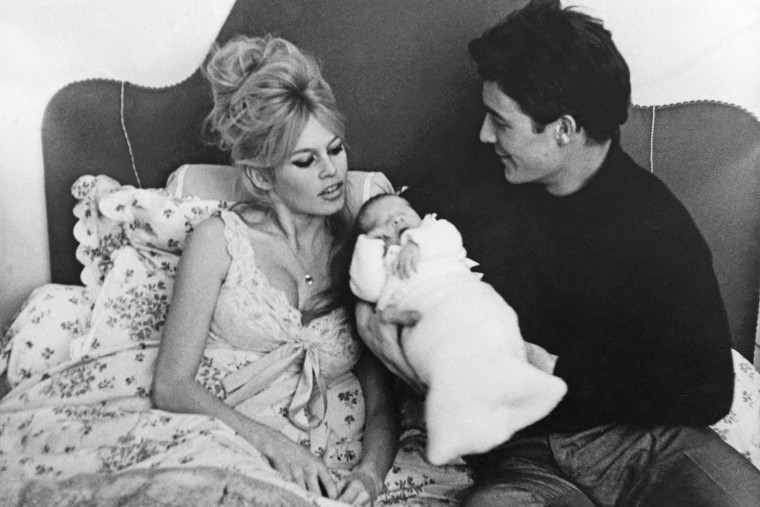

Two years later, Bardot married actor Jacques Charrier, with whom she had her only child — a son named Nicolas-Jacques Charrier, who was born in January 1960.

Bardot, in her memoir, wrote that she was “not made to be a mother.” She wrote that her unborn child was like a “cancerous tumor” that she tried to remove by punching herself in the stomach.

When that marriage broke up after three years, Charrier got custody of their son.

Father and son later sued Bardot for the “hurtful remarks” in the memoir and were awarded $36,200 in damages.

Bardot and her son, who lives in Norway, later reconciled. And she met her grandchildren and great-granddaughter.

Her three-year marriage to Sachs in 1966 was also marked by multiple infidelities, but it ended in an amicable divorce.

“A year with Bardot was worth 10 with anyone else,” Sachs reportedly said after the marriage was over.

Bardot, in public statements, rarely revisited her acting career once it was over. In a 2007 interview, she appeared to be at a loss when asked how she came to be an icon of French cinema.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I think that I arrived and left at the right time. My wild and free side unsettled some, and unwedged others.”