On my first long-haul flight, on a Boeing 747-200 when I was 4, the airline offered us a pile of gewgaws, presumably to keep the children quiet and out of the hair of the other passengers.

Among the toys was a red View-Master, with several discs depicting the airline’s operations, airport facilities and aircraft features for my edification, all in glorious 3D.

That View-Master is how I know that the upstairs section of 747 jumbos once housed cocktail lounges decorated in eye-watering 1970s orange for the more well-heeled jet-setter.

My dad explained that they created the 3D effect by taking two photographs from slightly different angles, one for each eye, to trick the brain into thinking it was seeing something real.

The device was known as a “stereoscope”, from a Greek word meaning “solid, three-dimensional”, and a Latin word meaning “to watch”.

The View-Master, unlike the Boeing 747 we were on, was not some new-fangled invention. The original View-Master was invented in 1939, only four years after Eastman Kodak introduced the Kodachrome colour film that made it possible.

The dream of 3D has always marched in lockstep with the invention of various new technologies to record, replay and view still and moving images.

Immersive experience

For as long as there have been moving pictures, inventors have dreamed of ways to make visual story-telling more realistic, to create a sense of truly “being there”.

From very early on, the dream was not only to lift images from their flat, still, two-dimensional constraints and make them move, but also to turn them into an immersive three-dimensional experience. Long before colour, sound or even film became part of the experience, moving pictures could be viewed in three dimensions.

The fundamental principles of 3D motion pictures date back to the 1830s, when Joseph Plateau developed a stroboscopic animation device variously known as the phantasmascope, fantascope or phénakistiscope, and a few years later, Sir Charles Wheatstone invented the stereoscope.

In the “Crystal Palace” of the Great Exhibition of 1851, visitors like Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Michael Faraday, Samuel Colt, Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, George Eliot, Alfred Tennyson and William Makepeace Thackeray could, alongside the world’s first public flush toilets, the world’s first soft drink (Schweppes) and the world’s first international chess tournament, treat themselves to a stereoscopic daguerrotype image of rising starlet, Queen Victoria.

To be fair to Queen Vic, she was no Luddite and readily sat for photographs. Both she and her husband, Albert, learnt how to take and develop their own photographic prints in the 1840s.

…article continues below…

The oldest surviving stereoscope images of Victoria are today housed in the London Museum. Note the slightly offset position of the camera for each image. When the images are displayed separately to each eye, the brain interprets them as a 3D image of the subject.

The Kinematoscope, or Motoscope, was patented in 1861, as an “improvement in exhibiting stereoscopic images”. It combined a stereoscopic viewer with the existing principle behind the phantasmascope, to create the illusion of 3D pictures in motion.

Not just some, but most early attempts to devise moving picture contraptions also tried to include a stereoscopic 3D effect.

Commercial film

American inventor Thomas Edison organised the first commercial exhibition of moving pictures on 14 April 1894, using celluloid film loops created by the prolific British inventor William Friese-Greene.

Edison used 10 models of the coin-operated Kinetoscope he had patented in the late 1880s “to do for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear”.

The Edison Kinetoscope consisted of a cabinet with a binocular peephole at the top, through which a viewer could look at the film. “Kinetoscope Parlors” rapidly became a franchise throughout the US.

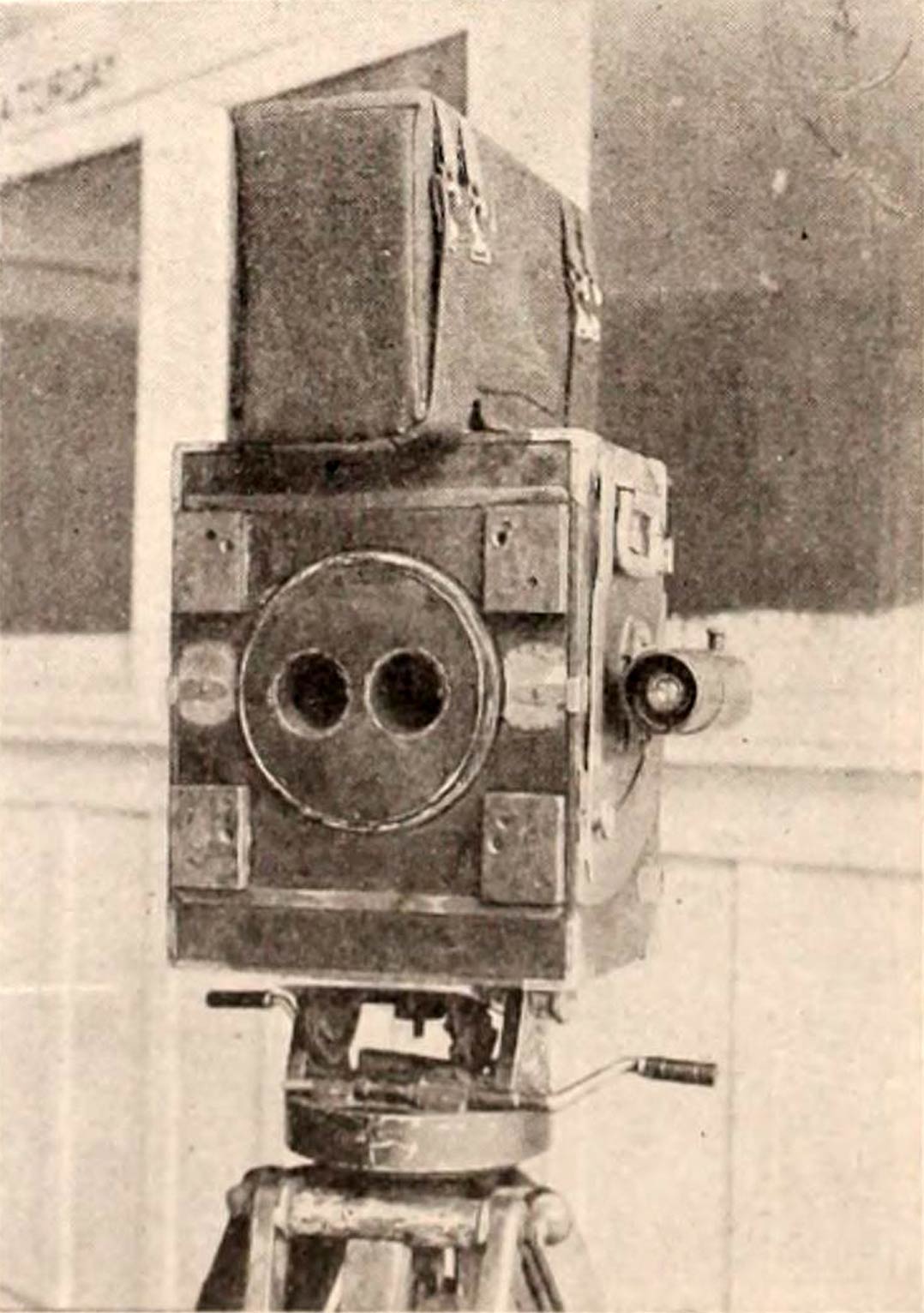

Right from the start, Edison’s plans included a stereoscopic version, and Friese-Greene filed a patent for a 3D movie process in 1893, using a camera with side-by-side lenses and two reels of film, which could be viewed through a stereoscope.

For reasons lost to time, Edison’s stereoscope plan never made it into production. That wouldn’t be the last failure for 3D moving pictures.

Edison also resisted pressure to develop a projection system, preferring the cash-generating slot machines he controlled. This left the field wide open to his rivals.

They included a pair of brothers who defected from his own workshop, Otway and Gray Latham, a pair of brothers in Berlin, Max and Emil Skladanowsky, and a pair of brothers in Paris, Auguste and Louis Lumière. (There was also a guy named Birt Acres in England, but he worked with Robert W Paul, who wasn’t his brother, so they don’t really count.)

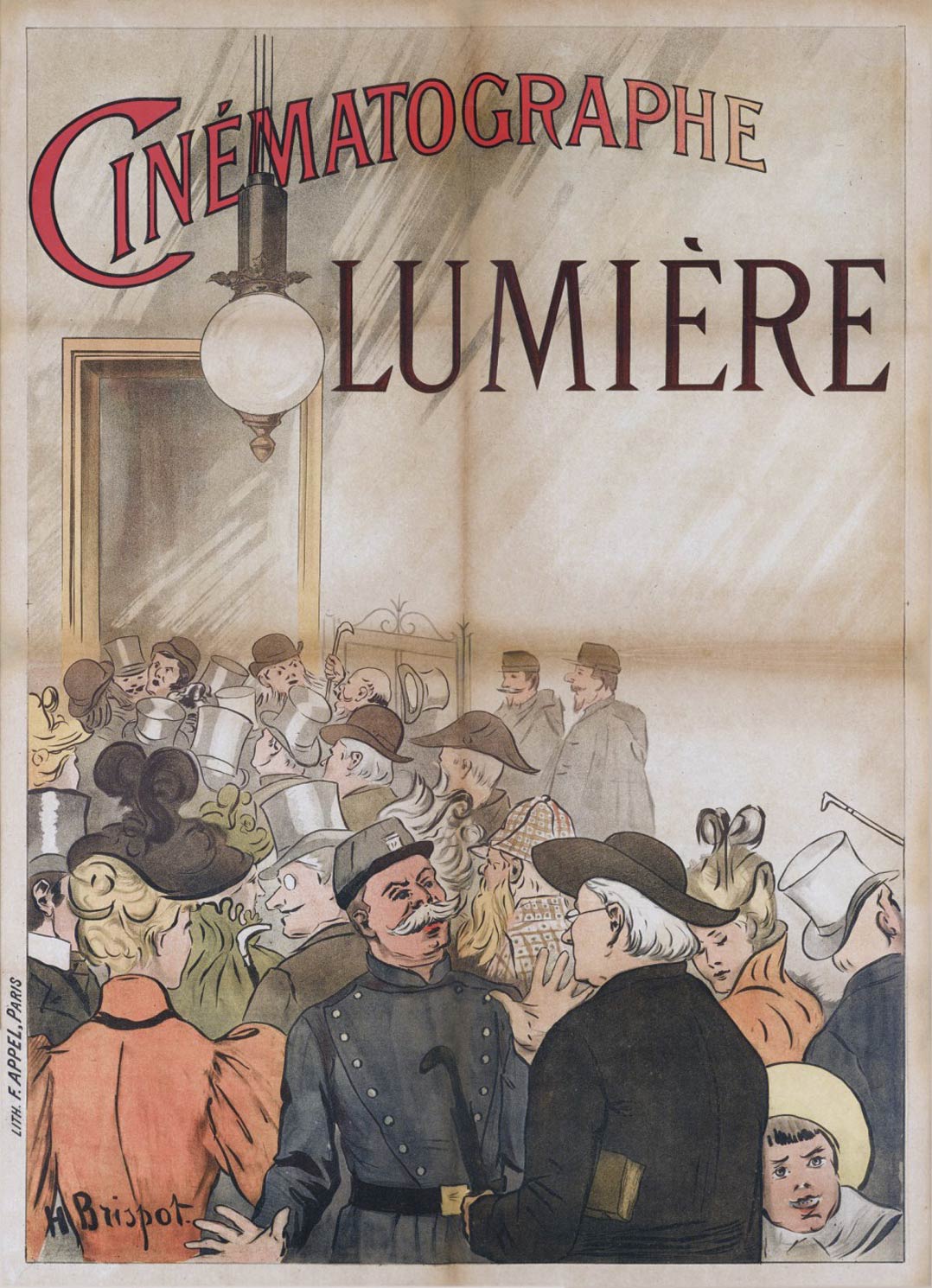

Although both the Lathams and the Skladanowskys had had projected films for commercial audiences earlier, their projector contraptions were not very good, and the Lumière brothers entered the history books as the fathers of modern cinema with a screening for 40 paying patrons on 28 December 1895.

…article continues below…

Many other inventors were contributing to the fast-developing field of film cinematography around the turn of the 20th century, and many of them worked on various techniques – ranging from Pepper’s Ghost-style illusions, to red-green or red-cyan anaglyph 3D that required glasses with different-coloured lenses of the kind a modern 3D enthusiast would recognise.

…article continues below…

Accidental 3D

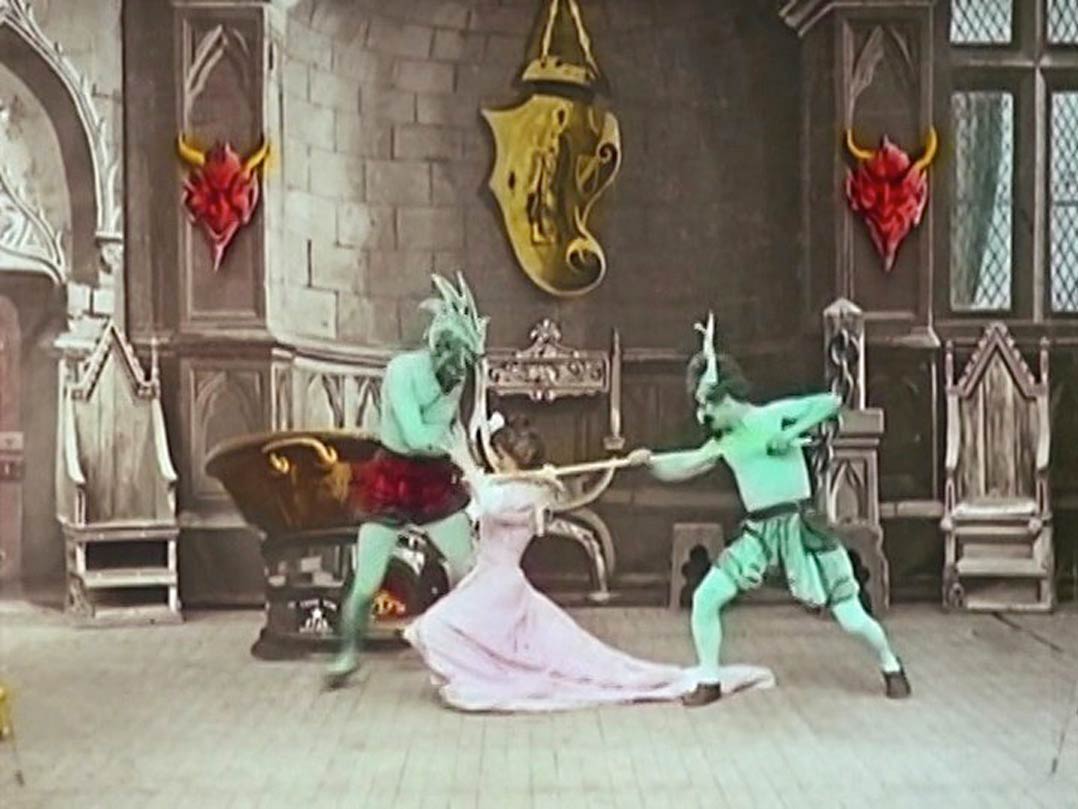

As early as 1903, Georges Méliès unintentionally created the first 3D films, when he devised a scheme to foil movie piracy. He built a camera with two lenses, to shoot two separate film reels, one of which was designed for domestic audiences and the other for foreign audiences.

It is unclear how this innovation stymied would-be pirates, but a century later researchers discovered that the two reels formed a perfect stereoscopic pair. In 2010, Serge Bromberg, the founder of Lobster Films, presented 3D versions of Méliès’s The Infernal Cauldron and another 1903 Méliès film, The Oracle of Delphi, at the Cinémathèque Française.

Most deliberate early attempts at 3D film were unsuccessful because, while the physics of 3D imagery was well understood, the solutions either produced low-quality images, or required expensive modifications to theatres, or required the audience to don inconvenient glasses.

If that sounds familiar, well, that’s because it is.

The first commercial 3D film was not Avatar, in 2009. It was not Jaws 3D from 1983.

It was not Prison Girls from 1972, though we can thank that particular side of the film industry for commercialising many technical innovations. They were the first to figure out a way to fill up an entire CD-ROM, pioneered online credit card payments and subscription services, and produced the first profitable virtual reality films.

It wasn’t Bwana Devil from 1952, or House of Wax from 1953, although those years were a golden age for 3D cinema, during which a long list of 3D films were produced, some of which were actually successful.

No, the first 3D film shown to a public audience is more than 100 years old: The Power of Love, a one-hour feature film made by Harry K Fairall in 1922.

…article continues below…

3D television

Television pioneers, like their cinematic counterparts, were from the start interested in 3D productions.

While American inventor Philo Farnsworth was busily working on the world’s first electronic television system, a Scottish engineer was doing interesting experiments with the mechanical television system he had built.

It is an open question whether Farnsworth, who demonstrated his system in 1927, or John Logie Baird, the Scot, who demonstrated the first true television imagery to the Royal Society and the press in 1926, ought to be given credit for inventing television.

In 1928, just two years after his initial invention, Baird demonstrated the first of a series of stereoscopic television systems, using both his electro-mechanical system and the electronic cathode ray televisions that had been developed across the pond.

Writing about stereoscopic television in Radio News in November 1928, RF Tiltman sounded very impressed with the “spectacular advances” in the field.

The idea of 3D television didn’t catch on, however.

Luring people back to theatres

The explosion of 3D films in the early 1950s was a strategy to lure people away from their living room televisions and back into theatres. For a year or two, this was fairly successful, but the campaign foundered on several rocks.

These were not unlike the rocks upon which 3D film had foundered before:

- Poor image quality;

- The expense of retro-fitting cinemas to accommodate 3D technology;

- The complexity of projecting two fully-synchronised films, even after the films have been used for a while and repaired;

- The need for eye-glasses when showing single-film anaglyphic 3D films;

- The fact that 3D films projected onto silvered screens were best viewed from straight ahead, but became blurry when viewed from either side of a theatre; and

- Complaints of eyestrain and headaches from the audience.

By 1954, the blockbuster film Dial M for Murder, produced in 3D by Alfred Hitchcock, was released in 2D because not enough cinemas were able to show films in 3D. It was a sign of the times, and sounded the death-knell of the 3D film fad of the 1950s.

Try, and try again

In 1981, Matshushita (now Panasonic) launched a 3D TV that used an active shutter system to create the illusion of depth. It worked with complicated glasses that used synchronised shutters to show alternate frames to different eyes, while blocking the other eye.

At standard television frame rates (30 frames per second in much of the world, and 24 frames in the rest), this produced awful levels of flicker and ghosting. The absolute minimum for tolerable quality required a 60Hz screen, and the image would appear flicker-free at 120Hz, which was well beyond the limits of the time.

Matshushita also owned Sega, which released a 3D videogame in 1982. Along with feature films like Friday the 13th Part III and Jaws 3-D, released in 1982 and 1983, another attempt was made to revive the 3D fad.

Although the films were more successful than the television, the novelty quickly wore off once again. It would take several more decades of technological development before 3D films of acceptable quality could be made.

21st century 3D

The most recent attempt at reviving 3D television followed the runaway success of Toy Story 3D and Avatar, in 2009. Audiences lapped them up as if 3D was the very essence of 21st century futurism.

Television makers took note. Many were casting about for ideas to bolster flagging sales. There was a widespread feeling that nobody really needed more than high-definition TV (that is, 1080p). Doubling that resolution to 4K seemed useful only for very large televisions that were way beyond the pockets of the average consumer.

Instead, manufacturers such as Samsung, LG and Sony began to roll out 3D TVs. At first, they required the familiar two-tint or differently-polarised 3D glasses, but soon, “auto-3D” technologies were developed based on miniature barriers or tiny refractive lenses in front of the image, to direct separate images to each eye.

At first, it looked like 3D TV was really going to make it this time. In 2010, 2.3 million units were sold. In 2011, that skyrocketed to 24.1 million units. In 2012, sales nearly doubled again, to 41.4 million units. Eighteen-fold growth over just three years made everyone very excited.

Broadcasters jumped on the bandwagon, and began to transmit movies, sports events, beauty pageants and shows like Strictly Come Dancing in glorious 3D.

By 2013 the party was already over, though. Sales of 3D TVs began to fall. The BBC announced that after its broadcast of a 50th anniversary episode of Dr. Who, it would indefinitely suspend 3D broadcasts due to “lack of public appetite” for the technology. Even people who owned 3D televisions weren’t particularly interested.

The production of 3D televisions largely ended in 2016, outside a handful of high-end devices made for die-hard fanatics.

The death of 3D

While 3D films in cinemas were moderately successful for a while, people just don’t watch television in the same way. They don’t sit down right in front of it and watch with full attention for however long a show lasts.

They walk around, do other things, and talk with friends and family. That’s hard to do when you’re wearing stupid 3D glasses, or when your TV screen becomes blurry from an angle.

Even in cinemas, however, 3D ran up against the same problems that has bedevilled the technology for over 100 years.

Whether in cinemas or in home televisions, 3D is expensive. Media designed for 3D is not readily viewable in 2D, and technology to make 2D media appear to be 3D produces results that are far from satisfactory.

People were still getting sick. Many viewers reported headaches, eye strain and even seizures. More than half of all people watching 3D movies got motion sickness as a result of the so-called “convergence-accommodation mismatch”, which is the discordance between the apparent origin of an image and where the eyes need to focus to see it. (Virtual reality headsets have the same problem.)

A significant minority of viewers couldn’t really see 3D images at all, because of various eyesight deficiencies.

Most importantly, perhaps, 3D doesn’t really add that much to television or film.

What were they thinking?

The brain already constructs a 3D image from a 2D projection, simply by virtue of contextual hints like relative scale, occlusion and depth of focus. While 3D does add parallax to the visual cues that influence how the brain reconstructs images, it does not resolve the focus accommodation problem.

As it turned out, the television industry bet entirely wrong: 4K really was the next big thing in television, and 3D never would be.

A simple glance at the history of 3D could have told them that before 80 million people got to regret buying a 3D television instead of a 4K panel. What were they thinking? — (c) 2025 NewsCentral Media

- Main image: A rugby player appears to emerge from the screen of a 3D television (AI-generated using Google Gemini)

Get breaking news from TechCentral on WhatsApp. Sign up here.